August 2023

The Power of Volunteers at Preston’s Springs Park

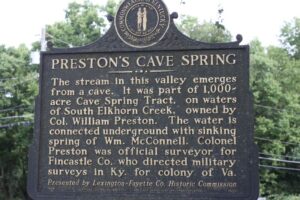

Preston’s Springs Park is unique among Lexington’s 100+ city parks. It does not have a single basket ball hoop, swing set, picnic table or even a bench. There is no asphalted walking path, not even a parking lot. A historic marker at 1937 Dunkirk Drive hints at its existence, and that is it for amenities. This narrow, entirely wooded area encompasses the flood plain of a naturally flowing creek in the Wolf Run watershed. The creek emerges from a cave that connects its waters to McConnel Springs further up in the watershed. It empties into Wolf Run near the intersection of New Circle Road and Old Frankfort Pike. The creek may constitute the longest stretch of water in Lexington that has not been altered through engineering to accommodate urban planning. Nor has the creek carved a deep gully for itself as our city streams commonly do when their banks are stripped of the woody vegetation that prevents erosion. It is the unaltered meandering flow of water over limestone bedrocks, so characteristic of natural waterways in the Bluegrass, that makes this creek and its park into a hidden gem.

This narrow, entirely wooded area encompasses the flood plain of a naturally flowing creek in the Wolf Run watershed. The creek emerges from a cave that connects its waters to McConnel Springs further up in the watershed. It empties into Wolf Run near the intersection of New Circle Road and Old Frankfort Pike. The creek may constitute the longest stretch of water in Lexington that has not been altered through engineering to accommodate urban planning. Nor has the creek carved a deep gully for itself as our city streams commonly do when their banks are stripped of the woody vegetation that prevents erosion. It is the unaltered meandering flow of water over limestone bedrocks, so characteristic of natural waterways in the Bluegrass, that makes this creek and its park into a hidden gem.

One might think that the woods flanking the creek would have retained a forest floor covered with our characteristic wildflowers, ferns and native shrubs asserting themselves along the creek or in the occasional small clearing. Unfortunately, that is not the case at Preston’s Springs. Just like other unmaintained natural areas in Fayette County, this park has been invaded by wintercreeper and bush honeysuckle on a massive scale. The park was established in 1988 when the city bought the land from a private owner. Apparently, it remained entirely unmanaged. When Roberta Burnes and John Walker “discovered” it, they found what was essentially a dumping ground for industrial debris, car engines, couches, refrigerators and all the other detritus of modern consumer life. Beginning around 2002, Roberta took it upon herself to organize volunteers and a series of dumpsters to get the debris out of there over a number of years. It was an audacious and huge undertaking. A follow-up effort by James Dickie and Bruce Hutchinson continued the debris cleanup. Later, other individuals and groups began to tackle the invasive plants. The Friends of

Wolf Run received a succession LFUCG Water Quality Incentive Grants to employ an ecological restoration firm, Skybox Inc, owned by Gary Libby, to work in the flood plain removing bush honeysuckle and introducing plants native to Bluegrass riparian zones. For the last six years, a small volunteer group, led by Jerry Weisenfluh, has removed invasives and planted natives on the slopes higher up. This group, which includes Wild Ones members Jannine Baker and Jerry Davis, meets once a week, works year-round and has made a tremendous impact already, with clear indicators of what the entire park may look like some day in the future. Again, Preston’s Springs is unique. The LFUCG Division of Parks and Recreation is only minimally involved in its operation, though the park is officially under its umbrella. Decisions about the park are essentially made by the volunteer and professional ecologists who work with the Friends of Wolf Run. These small groups have experimented with invasive plant control and developed effective approaches to honeysuckle and wintercreeper removal. They have engaged in interesting and fruitful discussions about the plants that should grow in our inner Bluegrass region. And while their work is of great benefit to the Cardinal Valley neighborhood, the city of Lexington and our local natural restoration community, they carry out their tasks without a great deal of fanfare.

Beate Popkin

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

May/June 2023

So, you want to make a pollinator garden………

………..or, in other words, you want to become a native plant gardener. And you have already decided which one of the many preoccupations of your current life you will let go, so that you can make room for this exciting new activity. For you know that gardening will not succeed for you, if you just add it as another duty to an already very busy life. Here is how you can start.

Select a small piece of ground on your property that is adjacent to the wall of your house, or to a fence, or to a patio, or to another garden bed, or to a walkway or to the driveway – just not in the middle of your lawn with grass all around. A good size might be 5×10’ though it certainly doesn’t need to be rectangular. Kill the grass. There are 3 methods for doing this:

- Strip the turf off the ground with a shovel after a rain

- Spray it twice with glyphosate (Roundup) – the second time 10-14 days after the first spray; you can start planting the day after your second spray.

- Lay cardboard or ripped open yard waste bags on the grass and cover that with mulch (this method takes 8 weeks to kill the grass when started in spring or summer; it takes all winter when started in the fall).

While you wait to plant, seek out plant exchanges or plant sales by garden clubs etc. Try to befriend other gardeners who can give you plants that they have extra. A friend of mine once said: “Whoever has a garden, has a nursery.” And it is true: every gardener has plants to give away, and the plants listed below are common in local native plant gardens. Volunteer to help maintain a public native plant garden; you will learn to recognize plants and you will go home with free starts for your own garden. You do not need to buy all your plants with a fully established root system. Those roots will readily grow in your garden if you give them a good start. Take note how much sun your chosen flower bed gets after the trees leaf out. If your bed is mostly sunny, plant the following (listed in succession of bloom; T means 3-4’ tall, and these should go toward the back; S means 1-2’ tall, and these should go toward the front; numbers indicate the quantity of plants; if more than one is mentioned they should be grouped in a cluster):

- 1 eastern bluestar (T)

- 1 Small’s beardtongue (S)

- 1 Showy primrose (S)

- 1 clump meadow phlox (S)

- 5-7 smooth beardtongue (T)

- 1-3 lanceleaf coreopsis (S)

- 1 slender mountain mint (S-T)

- 1 butterfly milkweed (S)

- 1 garden phlox (T)

- 1 clump blackeyed susans (S)

- 1 clump mistflowers (S)

- 3 grey goldenrod (T)

- 1 aromatic aster (T)

If your flower bed is mostly shady, plant the following. Your shade garden will have lovely blooms in the spring, no blooms in the summer and a few blooms in the fall.

- 1 bloodroot (S

- 3 Virginia bluebells (S, not grouped in a cluster)

- 1 merrybells (S)

Virginia bluebells and celandine poppies - 3 celandine poppies (S)

- 1 ragwort (S)

- 3 foam flowers (S)

- 3 Jacobs Ladder (S)

- 1 wild ginger (S)

- 3 false Solomon’s seal (T)

- 3 golden Alexander (S-T)

- 3 native columbines (S-T)

- 1 sensitive fern (S)

- 1 or 3 white wood asters (S)

- 1 snakeroot (T)

- 1 Short’s aster or heart-leaf aster (T)

After planting, water twice weekly for 3 weeks if it doesn’t rain; after that, water when the soil gets dry. During the first year, your plants will establish themselves and you have to be patient with them. The second year will be their best year. During the third year, your bed will change as seedlings from your plants germinate and you’ll have to decide which to keep and which to weed. This is when you start sharing plants with other gardeners. Observe your flower bed: how does it fill in? Are the colors pleasing? What spreads, what forms clumps, what mostly blooms on stalks (most spring wildflowers bloom close to the ground).

Above all observe yourself: Are you eagerly going out every other day to look at your bed, pull a weed or two, and watch the flowers open from bud to full bloom? Do the pollinators that come to your flowers actually interest you? How anxious do you get when a plant doesn’t seem to take off? When a plant dies, is that discouraging or can you see it as an invitation to find something different? Are you looking forward to expanding your bed? Are you going on garden tours, to the Arboretum, or to other public gardens to see how others approach this new hobby of yours? Do you visit garden centers to find out what else is available, leaf through catalogues or websites? Does your flower bed give you joy? If you feel good about spending time with your flower bed, you are on your way to becoming a gardener. If it feels like a burden, or if it is mostly irrelevant to your life, then this is probably not for you.

Beate Popkin

______________________________________________________________________________________

March 2023

Speaking to the Future with Loppers and Hand Saws

by Gabriel Popkin

Earlier this week I left my house, walked down the street and started snipping branches off of trees growing between the sidewalk and the roadway. When I encountered a limb too stout for my loppers, I grabbed a hand saw. Within a couple of hours, there were piles of branches up and down the block. On its surface, the activity feels mundane. What could be more prosaic than pruning a few trees? But lately, I’ve begun to ask the opposite question: What could be more profound?

There’s a temptation to think that all we need to do for trees is stick them in the ground. But that couldn’t be farther from the case: To live full lives, especially in cities where we ask them to grow in conditions far removed from the forests where they’ve evolved, trees need our continued attention and care. And of all the things we can do for trees, I’ve come to believe that pruning is one of the most durable actions we can take — and one of the most powerful ways we can speak to the future. So I’m here to convince you that tree planting as a solitary act has been oversold and overhyped. Pruning, my friends, is where it’s at. To be clear, tree planting is wonderful and important work. I’ve been involved in the planting of hundreds of trees, mostly in the town where I live outside Washington, DC. I’m sure I will plant many more trees. But tree planting is also overrated, because it’s so often framed as a one-time, commitment-free action that singlehandedly addresses a problem. It’s not. If a tree is planted but not cared for, especially in a city, it will probably grow poorly, live a truncated life and fail to provide much benefit for anyone. In fact, it may do more harm than good, saddling cities with maintenance costs they can’t afford and potentially turning residents off of trees for decades to come. Don’t just plant. Prune! So instead of planting trees this winter, I’m pruning them. And, perhaps not surprisingly, I feel especially drawn toward the trees near my house. I, along with other volunteers on my neighborhood’s tree commission, planted many of these trees in 2018. For one especially tree-deprived block, we chose a mix of more than a dozen species: basswood, baldcypress, tulip poplar, red maple, red oak, swamp white oak, redbud, hackberry, sycamore, willow oak, bur oak, river birch, fringe tree.

Five years in, our trees are starting to look like real trees, though still somewhat awkward and gangly. In human terms, they’re a bit like middle-schoolers: growing into their mature selves, but not yet ready for full independence. We still have work to do. I’ve learned over the years that planting a tree is easy, and growing a tree to its full potential is much harder. And because it’s hard, it’s also way more exciting. That’s because every tree offers an intellectual puzzle combined with a physical challenge. My job is to figure out what the tree needs and then carry it out. One might need lower limbs removed, so it can direct its resources toward growing upward. Another might need help “deciding” which of two competing upward-pointing branches should be the “leader” — in other words, one branch should be snipped off or shortened so the other can take the lead. A third tree might need some interior branches snipped off so they don’t create a weak structure or rub against each other, which can open wounds where disease can get in. A fourth may need all of the above. I realize this may all seem like helicopter tree parenting. Trees grow in the forest just fine without human help, we’re often told. Can’t they grow just as well in cities? It’s important to remember that the trees we’re growing in cities are wild species. With few exceptions, they were not designed or bred to grow in urban environments. (And most of those exceptions, such as the Bradford pear, have fallen out of favor.) We’ve plucked our urban trees from the forest and asked them to do things they did not evolve to do: live for decades in tiny spaces surrounded by pavement and provide us city dwellers with shade, beauty, cooling, health benefits, happiness. It’s amazing that wild forest trees grow at all in the puny boxes of compacted soil we offer them, much less that many seem to thrive there. It’s easy to imagine a world in which trees thrust into such environments simply shriveled and died. In the forest, a tree’s life is shaped by its neighbors, who force it to grow skyward with one main stem reaching for the light. Trees in forests self-prune as they grow, shedding lower branches when they no longer capture enough sunlight to be worth the metabolic cost of maintenance. Trees in cities, freed from competition, often “forget” to self prune or form a leader. Instead, they grow branches outward, often horizontally. They’re seeking light, and when you have no one above you, going out gets you more than going up. But that’s not what we want. We want our trees to become strong, stately, shade-casting giants that will endure for decades — and to avoid conflicts with pedestrians and delivery trucks that tend to end poorly for trees. So we need to assume the role of arboreal forest neighbors and shape our trees. It’s a daunting task. Some of the trees I’m pruning are already several times my height, and they’re just getting started. Some could — should — outlive me. With luck, they will improve the lives of people who aren’t even born yet — people I will never know. As the world warms, they will become ever more important. To have so much at stake is almost overwhelming. To think I can meaningfully shape the lives of such massive, long-lived beings can feel like the height of hubris. But then I remind myself, if I don’t do it, who will? Our small city has almost no money to pay someone to care for trees, and my fellow volunteer pruners are busy in other parts of the city. So I put my doubts aside, pick up my tools and get to work. Speaking to the future I fear that only a small fraction of the millions, billions or trillion trees planted will get this kind of care. I’ve seen countless grants for tree planting. I can’t recall ever seeing a grant for tree pruning or long-term care, even though pruning can account for 40 percent of a city’s tree-related expenditures — up to eight times the cost of tree planting. (That’s mostly pruning of big trees with machines, not the early structural pruning I do from the ground, but structural pruning can reduce future maintenance costs.)

Thanks in large part to my neighbor and tree pruning mentor Barry Stahl, I think we in Mount Rainier, almost by accident, have stumbled upon a model of community-led tree care that works, if perhaps not perfectly, as well as any city program I’m aware of. It requires a special combination of factors: a skilled leader (Barry), a critical mass of motivated volunteers and a city government willing to trust its residents (possibly a reflection of limited resources). Tree commissioners and several others are authorized to prune public trees, including street trees. Hundreds of people walk by our trees every day. Sometimes dogs poop on them and occasionally one is vandalized, which can be distressing. Few people probably give them — or their caretakers — much thought as they hurry about their lives. But we do. Barry put this beautifully and profoundly the other day, when he said, “We have a duty to these trees and to the community. But we also have a privilege. Nobody else gets to look at them and know them the way we do.” These trees are real, physical beings. I can run my hands over their bark, smell their flowers, brush their leaves against my cheek. When I prune them, they respond; if I’m attuned to these responses, I can care for them better. It’s a positive feedback loop. I believe we are meant to interact, physically and meaningfully, with the world. We are not just brains in jars, as much as the online life can give that impression; we are bodies with senses, muscles, nerve endings. For many of us, our bodies are so underutilized that we need to invent reasons to exercise them. Pruning trees is meaningful bodily work. It awakens ancestral connections between human bodies, tools and wood: three things that have been in contact and communication for as long as our species has existed. Soon, perhaps as soon as next year, some of the trees I’ve been pruning will grow beyond my reach. Like a parent sending their child off to college, I will have to let them go, trusting them to take care of themselves. I already feel wistful.

Gabriel Popkin, a Lexington native, is a free-lance journalist writing about science, nature and the environment. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Science, Nature and other national publications. He lives in Mt. Rainier, Maryland, just across the street from the Washington DC border. A longer version of this article appeared at his Substack _______________________________________________________________________________

February 2023

Fostering Plants

by Beate Popkin

It’s a new year and it comes with new hopes, new ambitions, new projects. Our Wild Ones chapter has put together the program for 2023, and its focus is on plants. We will look at plants during garden visits, talk about plants during our program events, and, yes, eradicate plants that undermine natural diversity. Plants are the basis of life. They feed the animals (mostly herbivores) that comprise the vast majority of species in the animal kingdom. Other animals (mostly carnivores) sustain themselves on a diet of plant eaters. We humans, along with some other animals, are omnivores, which means we can digest plants as well as the meat and other products derived from animals. While our dietary options are vast, plants are still at the basis of all of them. Without plants, we would not exist. Plants also keep our earth habitable by sustaining a climate that makes it reasonably comfortable for us to live on it. Or at least they did so until recently, for we now fear that our planet will soon become a place unsuitable for human habitation. And we suspect that plants will be around less and less to help us bear up under heat, cold, drought and devastating storms, because we have altered the land which has been their habitat. The truth is, for all the benefits we derive from plants, we don’t treat them with much respect. They don’t fit well into our urban lives where we arrange ourselves surrounded by walls and pavement. When we plant them in the environments that we have created to suit ourselves but that are inhospitable for them, we nevertheless expect them to gratify us without giving them much care. We don’t often ask ourselves: in what sort of natural habitat did this plant evolve? Wild Ones is, of course, uniquely positioned to promote caring for plants. But do we really want to do that? Or do we still chase after a “low-maintenance” landscape, when we engage ourselves with plants? Are we hanging onto the dream that nature will basically take care of itself?

Plants also keep our earth habitable by sustaining a climate that makes it reasonably comfortable for us to live on it. Or at least they did so until recently, for we now fear that our planet will soon become a place unsuitable for human habitation. And we suspect that plants will be around less and less to help us bear up under heat, cold, drought and devastating storms, because we have altered the land which has been their habitat. The truth is, for all the benefits we derive from plants, we don’t treat them with much respect. They don’t fit well into our urban lives where we arrange ourselves surrounded by walls and pavement. When we plant them in the environments that we have created to suit ourselves but that are inhospitable for them, we nevertheless expect them to gratify us without giving them much care. We don’t often ask ourselves: in what sort of natural habitat did this plant evolve? Wild Ones is, of course, uniquely positioned to promote caring for plants. But do we really want to do that? Or do we still chase after a “low-maintenance” landscape, when we engage ourselves with plants? Are we hanging onto the dream that nature will basically take care of itself?

As urban or ex-urban dwellers, our easiest place to foster plants is in gardens, parks and nature preserves. All these places hugely need our care, our engagement, our interest, our wanting to know and understand the plants that grow there. Gardens are perhaps most the obvious places to be engaged with plants and nature. We can choose to plant the natives of our region that respond well to the soil and climate conditions where we place them. If they are happy, they will spread around by seeds or rhizomes. We’ll manage the competition from weeds as well as the competition in which they live with each other. Observing their natural habits, promoting their well-being, and helping them get along with their neighbors are the tasks of the gardener, and those tasks can be endlessly fascinating. In parks, urban greenspaces and nature preserves our ability to care for plants is much more circumscribed. The spaces are usually large and sometimes vast. In order to be involved we need to cooperate with others, but that provides opportunities for friendships and for building communities. Plant care in public spaces also requires abiding by the regulations of the entities that are in charge of them. While their rules may hem in our visions, they also provide stability for our efforts and the promise that the results of our work will last into the future.

The greatest threat to the well-being of our plants are invasives: fungi, animals, and other plants introduced from far away continents. They can kill whole species of plants outright as the chestnut blight did in the last century to a North American tree of tremendous ecological significance. More recently the emerald ash borer, has been doing the same to our native ash trees. Invasive plants introduced from elsewhere can also pose a significant threat to our native plants and their habitats. The inner Bluegrass where we live is ravaged by wintercreeper (Euonymous fortunei) which aggressively invades every nook and cranny of soil. It densely covers the ground and climbs up on trees, fences and human-made structures, where it flowers and produces seeds that the birds carry far and wide. Bush honeysuckle is our second most severe ecological threat. Both these two plants, when well establish which happens quickly, will cover a piece of ground so densely that they form a complete monoculture and other plants cannot grow there. These are the spaces that are most in need our intervention, restoration and care. Fosterin plants takes work and effort. We left the Garden of Eden with its self-sustaining landscape a long time ago. But its plants are still with us. In fact, they are close at hand. If we are prepared to care about them and to care for them, they will reward us in a multitude of ways. They will unfold their beauty to us and they will make our environment come to life again.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

November 2022

Reflections on a Dry Fall: To Water or Not to Water

For gardeners the lack of rain in the last 2 months has been a matter of concern. With every forecast of another week of nothing but sunny days, hopes for a lush colorful fall flower garden faded. Asters still bloomed but not for long, and the same with the goldenrods, snakeroots, the mistflowers and all the others. These plants moved quickly from flowering to seed production in an effort to efficiently harness their reserves of moisture. There has also been the worry that young trees and shrubs may simply die or be seriously damaged by the drought; that they might not come back with their usual vigor next spring, or not come back at all. So, many gardeners asked themselves: should I water or not?

It is good to remember that a dry fall is the norm for us rather than an exception. September and October are typically the months of lowest rainfall. But in years past, we have often gotten some relief from the fall-out of distant hurricanes as they pounded the gulf and east coasts in September. This year the big devastating hurricane that brought so much destruction to Florida passed us by entirely. We often proclaim that native plants are superior garden plants because they are adapted to our climate. If we take this statement seriously, it follows that they can cope with a dry Kentucky autumn. But what does “cope” mean? For herbaceous plants it means getting through the business of flowering, setting seed and dispersing them so that their species can continue. When this task is accomplished, their stalks die. Woody plants keep live structures above ground as they settle into dormancy, but they withdraw sap and nutrients from them to be stored in their roots during winter. In the temperate zone where we live, the lowering of rainfall during fall, together with the reduction of warmth and light, signals to plants that they better get on with the tasks of autumn. As gardeners, we expect them to do this in a graceful manner. Fall reminds us of death, of course, and in our gardens we want this to be a beautiful death. We hope for two months of color bursts, and only then are we ready to let go. But the plants may have a different agenda. When stressed by drought, fall-flowering herbaceous plants will speed up setting their seeds, and we may not get more than a few days of good bloom out of them. Woody plants under draught stress may sense that it is to their advantage to go dormant early; their leaves may dry up and drop without going through the color change we expect. It all makes sense from the plants’ point of view. A friend of mine who is dedicated to native plant gardening claims that she never waters: “they are natives, they should be able to live through these conditions.” Well, yes and no. They are natives, but if they grow in a garden they did not choose their location: in disturbed ground, compacted by construction equipment and lawn mowers. They may need our help to live in less then favorable conditions, and in the fall this may mean giving them some extra water. Also, in nature a plant is likely to survive a period of unsuitable weather. But in a garden, simple survival may not be enough. We want our plants to thrive so that they can give us visual pleasure. So a little help from the hose may be good for a native plant that is expected to perform in a garden setting.

As gardeners, we expect them to do this in a graceful manner. Fall reminds us of death, of course, and in our gardens we want this to be a beautiful death. We hope for two months of color bursts, and only then are we ready to let go. But the plants may have a different agenda. When stressed by drought, fall-flowering herbaceous plants will speed up setting their seeds, and we may not get more than a few days of good bloom out of them. Woody plants under draught stress may sense that it is to their advantage to go dormant early; their leaves may dry up and drop without going through the color change we expect. It all makes sense from the plants’ point of view. A friend of mine who is dedicated to native plant gardening claims that she never waters: “they are natives, they should be able to live through these conditions.” Well, yes and no. They are natives, but if they grow in a garden they did not choose their location: in disturbed ground, compacted by construction equipment and lawn mowers. They may need our help to live in less then favorable conditions, and in the fall this may mean giving them some extra water. Also, in nature a plant is likely to survive a period of unsuitable weather. But in a garden, simple survival may not be enough. We want our plants to thrive so that they can give us visual pleasure. So a little help from the hose may be good for a native plant that is expected to perform in a garden setting. Beate Popkin

Beate Popkin

_______________________________________________________________________________

October 2022

Snags

When a tree dies in the forest, it does not immediately collapse; instead it decays while standing in place for a few years, continuously dropping its smaller branches to the ground. It’s Nature’s way of forest management, for the snag, which is what the dead tree is called, provides countless benefits to wildlife and to a woodland’s ability of regenerating itself. Birds, bats, squirrels, racoons and other animals make their nests in the crevices and hollow cavities of snags. Insects, mosses, lichens and fungi that thrive in dead wood provide food for woodpeckers, nut hedges, song birds and small mammals. Squirrels and other animals use snags to store food that they gather in the fall. Tall snags become perches from which raptors survey the forest and dive for prey.

Eventually, the snag collapses into a heap of decaying wood lying on the ground. But that is not the end of the tree’s beneficial presence in the world. The mosses, lichens and fungi living in that heap of disintegrating wood help to return vital nutrients to the soil through the nitrogen cycle. And the decaying wood on the floor acts as a “nurse log” for new tree seedlings offering them the rich nutrients they need to get established.

Of course, a suburban garden or even a city park is not a forest. And while snags can provide the same benefits in urban environments, they will need to be managed. It is not a good idea to leave dead branches high up in a tree where they can fall on people or structures below. So, usually only the trunk of a tree makes a good urban snag.

The photos here document the transformation of a tree that in 2017 still had some life in it but in 2022 turned into a heap of decaying wood on the ground. When the Idle Hour Neighborhood planted a stream buffer in the greenspace along a branch of West Hickman Creek, four silver maples grew there. Two of these are still alive, but the other two were too far gone to be saved. City arborists cut off all their branches in September 2017, leaving the trunks standing to slowly decay in place. The smaller and weaker one collapsed on September 19, exactly five years after it had been reduced to a snag.

Beate Popkin

______________________________________________________________________________

September 2022

Porcelainberry Vine

An Invasive Coming toward a Greenspace near you

The title of this essay may be misleading. Porcelainberry is not an invasive far away on the horizon – it may already be established in your local park, and it is possibly growing in your garden as well. Perhaps you are mistaking it for a grapevine, a resemblance that could explain why it has spread under the radar, without causing much concern. However, when its berries ripen, which happens from August to October, all illusion lifts and the plant shows its true colors, literally speaking. To our naturalist’s eye, those colors may seem too pretty to be true, indicating that the plant does not belong here. But they also explain why previous generations of gardeners and horticultural entrepreneurs were seduced by the vine and began introducing it from east Asia in the 1870s. Those changing hues are stunning indeed: green, white, pink, lavender, purple and, yes, porcelain blue, all on display simultaneously as the berries mature. What’s not to like about something so pretty? Well, for starters, porcelainberry has escaped cultivation and established itself in natural areas, because its seeds readily germinate even in competitive situations. It is a perennial woody vine that grows fast, up to 15 feet per season. Its stems branch freely so that it can cover large areas of ground and suppress other vegetation. When it finds a tree or large shrub it attaches itself to their smaller branches with tendrils and its weight can cause ice and wind damage to a tree as it flops around at great height. It has been known to kill trees. It grows in sunny or partially shaded locations and thrives in moist areas along creeks, ponds and lakes. Therefore it is particularly prone to invade the vegetative buffers and no-mow strips that nowadays often replace mowed turf grass along the edges of streams. Of course, we must protect urban streams from erosion by sustaining plant buffers that keep their banks in place. But since little regular maintenance tends to occur along a stream once it has received its no-mow designation, these buffers become a breeding ground for all sorts of invasive plants. Poison hemlock has spread in such habitats seemingly unchecked and is very visible in early June when it flowers. Porcelainberry is begging to be noticed right now, in September, as its seeds ripen.

To our naturalist’s eye, those colors may seem too pretty to be true, indicating that the plant does not belong here. But they also explain why previous generations of gardeners and horticultural entrepreneurs were seduced by the vine and began introducing it from east Asia in the 1870s. Those changing hues are stunning indeed: green, white, pink, lavender, purple and, yes, porcelain blue, all on display simultaneously as the berries mature. What’s not to like about something so pretty? Well, for starters, porcelainberry has escaped cultivation and established itself in natural areas, because its seeds readily germinate even in competitive situations. It is a perennial woody vine that grows fast, up to 15 feet per season. Its stems branch freely so that it can cover large areas of ground and suppress other vegetation. When it finds a tree or large shrub it attaches itself to their smaller branches with tendrils and its weight can cause ice and wind damage to a tree as it flops around at great height. It has been known to kill trees. It grows in sunny or partially shaded locations and thrives in moist areas along creeks, ponds and lakes. Therefore it is particularly prone to invade the vegetative buffers and no-mow strips that nowadays often replace mowed turf grass along the edges of streams. Of course, we must protect urban streams from erosion by sustaining plant buffers that keep their banks in place. But since little regular maintenance tends to occur along a stream once it has received its no-mow designation, these buffers become a breeding ground for all sorts of invasive plants. Poison hemlock has spread in such habitats seemingly unchecked and is very visible in early June when it flowers. Porcelainberry is begging to be noticed right now, in September, as its seeds ripen.

So what to do? First of all, learn to recognize it and to distinguish it from our native grape vine. While both have leaves that are heart-shaped at the base, porcelainberry leaves are often, but not always, deeply dissected. Its stems remain light colored and smooth as they thicken, whereas grapevine stems are brown and have a shredded appearance. Also, the pith of the former is white, whereas grape vines have brown pith. Controlling porcelainberry probably starts with finding the spot where the original vine, the mother plant so-to-speak, emerges from the ground and cutting its main stem. Branches will probably be growing horizontally in different directions sending down roots where their nodes touch the soil. These branches should be pulled up as much as possible. When a substantial branch grows upward on a tree or fence it should be cut close to the ground. The wound created by any cut should be “painted” or sprayed immediately with a concentrated herbicide solution. If left untreated it will resprout quickly. This is good winter work for anybody who itches to be outside and has gotten a bit bored with honeysuckle or wintercreeper removal. Serious infestations of porcellain berry vine will have to be sprayed with a selective herbicide. In doing so, one would want to preserve the grasses along stream banks rather than create barren ground that invites weeds to move in. Therefore glyphosate (or Roundup) is not suitable; products containing triclopyr are often recommended.

Beate Popkin

__________________________________________________________________________

August 2022

American Natives Abroad

We Wild Ones feel virtuous about our commitment to native plants, and rightly so. But we rarely ask ourselves how our plants are received in other parts of the world. During my annual trips to Germany, I often come across familiar north American species and I begin to muse about the benefits and problems of human induced plant migrations. This summer, my husband and I rented an Airbnb in Berlin near the Bergmannstrasse, a busy street lined with shops and restaurants. Two blocks had recently been radically traffic-calmed. The street was divided into 3 lanes: one lane was open to bicycles going in both directions, another lane accommodated one-way traffic for deliveries and persons who lived there. The middle lane was given over to casual seating with chairs and benches surrounded by attractive metal containers from which tall plants sprouted looking both natural and pretty. Among the plants was our purple Verbena bonariensis. I was delighted to find this friend from home lending such grace to an imaginatively designed urban setting. The two blocks along this busy street accommodated movement, car-ownership, pedestrian traffic and Berliners’ ever-present need to take a break, to have a drink, to just sit, take in the sun, to observe the lively urban hubbub around, to fiddle with their phone or read a book. I like to think that the Berliners who shop or dine or simply hang out in the Bergmannstrasse, feel a warm welcome for this pretty though not very showy flower from our part of the world. More likely, though, they are pretty indifferent to the plant’s geographic origin. If so, that indifference seems not so casually extended to people from elsewhere. While the new plant containers were still free of the ubiquitous Berlin graffiti, one of them had already been adorned with this message: “Tourists go home!”

I like to think that the Berliners who shop or dine or simply hang out in the Bergmannstrasse, feel a warm welcome for this pretty though not very showy flower from our part of the world. More likely, though, they are pretty indifferent to the plant’s geographic origin. If so, that indifference seems not so casually extended to people from elsewhere. While the new plant containers were still free of the ubiquitous Berlin graffiti, one of them had already been adorned with this message: “Tourists go home!”

Everywhere in Germany I found a vine whose leaves were formed by five palmately arranged leaflets. In gardens it climbed on fences and walls and in urban parks it climbed on trees and lampposts. I asked a landscape architect what it is called in German. Oh, he said, that is a wild vine; which is the name Germans will assign to any climbing plant that doesn’t make grapes and whose name they don’t know. But, on reflection, he came forth with a more precise definition: Parthenocissus quinquefolia. Of course, I already knew that it was Virginia Creeper (but I still don’t know its German name, since the “wild vine” is firmly settled in people’s horticultural vocabulary). It covers all manner of surfaces adding much needed green in urban spaces that can overwhelm with concrete and brick. It is a north American native that has found a welcoming home in Germany. Not so our native wild cherry (Prunus serrotina), which was introduced to Europe in the 17th century. Its lustrous dark green leaves and white flowers born on pendulous racemes and followed by red fruit that turn black during summer recommended it as a desirable ornamental. While we cherish it as a host plant for many species of moths and butterflies, in Europe it is pretty much ignored by wildlife, which added to its ornamental value. But now it has become a maligned invasive in natural forests. I visited a state-of-the-art natural restoration display in the Grunewald, Berlin’s largest city forest. Eradicating the “late-flowering grape cherry” as it is called in translation, was a major effort underway in the Grunewald. The sign on the left illustrates the tree’s passage to Europe from North America, seemingly to France from Nebraska. Europeans, of course, had not reached the upper Mississippi in the 17th century, and the tree almost certainly came from somewhere near our east coast. Never mind, the central European climate, not dissimilar to our own, suited it perfectly and it has spread all the way to Russia. Beate Popkin

Not so our native wild cherry (Prunus serrotina), which was introduced to Europe in the 17th century. Its lustrous dark green leaves and white flowers born on pendulous racemes and followed by red fruit that turn black during summer recommended it as a desirable ornamental. While we cherish it as a host plant for many species of moths and butterflies, in Europe it is pretty much ignored by wildlife, which added to its ornamental value. But now it has become a maligned invasive in natural forests. I visited a state-of-the-art natural restoration display in the Grunewald, Berlin’s largest city forest. Eradicating the “late-flowering grape cherry” as it is called in translation, was a major effort underway in the Grunewald. The sign on the left illustrates the tree’s passage to Europe from North America, seemingly to France from Nebraska. Europeans, of course, had not reached the upper Mississippi in the 17th century, and the tree almost certainly came from somewhere near our east coast. Never mind, the central European climate, not dissimilar to our own, suited it perfectly and it has spread all the way to Russia. Beate Popkin

June 2022

Reforesting in the Bluegrass

For several years after 2015, when I had begun to periodically visit Hisle Park in northeast Fayette County, I was mystified by a property along Briar Hill Road where a very large number of young oaks grew in a dense plantation. In the winter and early spring, a house became visible at the end of a long curving driveway. What contrast to the surrounding pastures where horses grazed in expansive fields! Who created this planting and for what purpose? Then, in the summer of 2020, I met Ann Whitney Garner, the owner, and she invited me to her farm. On that first visit I drove through the opened gate with intense expectation and followed the driveway in awe at the extent of the plantation. The trees growing in rows stretched almost up to the residence. Ann Whitney showed me the garden, chicken coop, barn and tree nursery behind the house, then took me through a small natural woodland to a substantial creek, David’s Branch, that forms the rear border of the property. She and her husband Allen Garner bought this 20-acre lot in 2006. In 2008 they moved with their three school-aged children into their newly constructed home and engaged a landscape contractor to design and install the plantings typical of Bluegrass residences: many boxwoods, cherry laurels which are now dead, and more than 500 liriope plants which Ann Whitney has since dug up and discarded.

Then, in the summer of 2020, I met Ann Whitney Garner, the owner, and she invited me to her farm. On that first visit I drove through the opened gate with intense expectation and followed the driveway in awe at the extent of the plantation. The trees growing in rows stretched almost up to the residence. Ann Whitney showed me the garden, chicken coop, barn and tree nursery behind the house, then took me through a small natural woodland to a substantial creek, David’s Branch, that forms the rear border of the property. She and her husband Allen Garner bought this 20-acre lot in 2006. In 2008 they moved with their three school-aged children into their newly constructed home and engaged a landscape contractor to design and install the plantings typical of Bluegrass residences: many boxwoods, cherry laurels which are now dead, and more than 500 liriope plants which Ann Whitney has since dug up and discarded. The Garners do not come from farm backgrounds, yet they wanted to use their land for some kind of agrarian activity that would reduce the amount of mowing on their empty space. They knew that they did not want horses. They considered a vineyard but found out that their land was too alkaline. They played with the idea of growing corn or organic tobacco but had to acknowledge that they would get no return on their investment of money and effort. They knew that they cared about nature, and Ann Whitney anticipated the moment when her children going to high school and then college, which would free up time for a new kind of work. She couldn’t exactly define what it would be, but she wanted to work on her property. In 2010, she had an epiphany: “Why don’t we grow what’s supposed to be here,” she asked herself and her family. She had walked her property almost daily pondering what she observed: the way bush honeysuckle and winter creeper intruding from the perimeter suppressed the regeneration of plants, and the possibilities offered by the large expanse of open space. It occurred to her that the property called for trees, because that is what Nature would plant on it. Trees would create wildlife habitat, beauty and – in the very long term – financial value. The Kentucky Division of Forestry helped her move forward with her project providing several forest management plans, offering tree seedlings for a very reasonable price and eventually loaning her a mechanical tree planter. During the first year she ordered and planted 100 trees: many redbuds, some pecans, sycamores, and bur oaks. Then she put in an order of 300 trees, including many bald cypress for a low lying area. Then, in 2013, the Garners took a big plunge ordering 5000 oak seedlings, 1000 each of swamp white, bur, northern red, Shumard and chinquapin oak. They chose oaks knowing that they would be slow-growing and not immediately overwhelm them with labor-intensive management tasks. They also assumed that an investment in oaks can provide a financial return in the distant future when selective harvesting for some kind of a niche market may become feasible. Also, Ann Whitney had taken note of Doug Tallamy’s argument in Bringing Nature Home, that oaks are immensely valuable as habitat trees and a food source for a huge variety of caterpillars thereby sustaining a large bird population. When they ordered their 5000 oaks, the Garners knew from experience that this number could not be planted with shovels, and that is where the mechanical tree planter came in. Hitched to a tractor, it carves grooves in the ground where individual workers riding on the machine place bare root plants at regular intervals. The entire Garner family participated in planting the oaks which turned into a surprisingly efficient and gratifying project. Encouraged by their success with the oaks, they embarked on their last large planting endeavor two years later by installing 1000 tulip poplars in a remaining empty space behind the house. Ann Whitney had observed how fast the poplars grew and decided she wanted to speed along the development of a canopy cover on at least part of the property.

The Garners do not come from farm backgrounds, yet they wanted to use their land for some kind of agrarian activity that would reduce the amount of mowing on their empty space. They knew that they did not want horses. They considered a vineyard but found out that their land was too alkaline. They played with the idea of growing corn or organic tobacco but had to acknowledge that they would get no return on their investment of money and effort. They knew that they cared about nature, and Ann Whitney anticipated the moment when her children going to high school and then college, which would free up time for a new kind of work. She couldn’t exactly define what it would be, but she wanted to work on her property. In 2010, she had an epiphany: “Why don’t we grow what’s supposed to be here,” she asked herself and her family. She had walked her property almost daily pondering what she observed: the way bush honeysuckle and winter creeper intruding from the perimeter suppressed the regeneration of plants, and the possibilities offered by the large expanse of open space. It occurred to her that the property called for trees, because that is what Nature would plant on it. Trees would create wildlife habitat, beauty and – in the very long term – financial value. The Kentucky Division of Forestry helped her move forward with her project providing several forest management plans, offering tree seedlings for a very reasonable price and eventually loaning her a mechanical tree planter. During the first year she ordered and planted 100 trees: many redbuds, some pecans, sycamores, and bur oaks. Then she put in an order of 300 trees, including many bald cypress for a low lying area. Then, in 2013, the Garners took a big plunge ordering 5000 oak seedlings, 1000 each of swamp white, bur, northern red, Shumard and chinquapin oak. They chose oaks knowing that they would be slow-growing and not immediately overwhelm them with labor-intensive management tasks. They also assumed that an investment in oaks can provide a financial return in the distant future when selective harvesting for some kind of a niche market may become feasible. Also, Ann Whitney had taken note of Doug Tallamy’s argument in Bringing Nature Home, that oaks are immensely valuable as habitat trees and a food source for a huge variety of caterpillars thereby sustaining a large bird population. When they ordered their 5000 oaks, the Garners knew from experience that this number could not be planted with shovels, and that is where the mechanical tree planter came in. Hitched to a tractor, it carves grooves in the ground where individual workers riding on the machine place bare root plants at regular intervals. The entire Garner family participated in planting the oaks which turned into a surprisingly efficient and gratifying project. Encouraged by their success with the oaks, they embarked on their last large planting endeavor two years later by installing 1000 tulip poplars in a remaining empty space behind the house. Ann Whitney had observed how fast the poplars grew and decided she wanted to speed along the development of a canopy cover on at least part of the property.

With the restoration of the Bluegrass underway, birds became more abundant and the soil began to absorb water more readily due to the expanding roots that channel it into the ground. But with the planting done, new questions arose: How does one live as a good steward on a property into which one has invested so much time, energy and money? Does the property lend itself to other uses that are still compatible with the goal of sustaining Nature? In 2019 Ann Whitney started a tree nursery. Having handled thousands of tree seedlings over almost ten years, she concluded: “I can do this myself.” She studied up on propagation techniques and collected seeds of native trees growing in the Bluegrass. She wants to inspire other property owners to follow her example restoring the Bluegrass, creating habitat for wildlife and helping the soil heal. She would like to make resources available to help them get started, and first and foremost among these are young trees. At this point her nursery has a number of native species available in 3 and 5 gallon containers. Her website is https://www.fieldstoforest.com/. Many landowners in Kentucky live on properties that they do not imagine ever returning to agricultural use. In Fayette County a single residential house can be built on 20-acre lots outside the urban service boundary with the official explanation that it serves agricultural activities, even though there is rarely any evidence of it. Instead, one drives past large lots with a house in the distance, possibly a few trees here and there, but otherwise with the ground covered in turf grass subject to a relentless mowing regime. It doesn’t have to be this way. Ann Whitney Garner let her land speak to her. She walked on it and she worked on it. And she reflected on what she saw. She considered agricultural ventures. She became interested in ecology reading about plants and the animals they sustain. She sought professional advice and consulted with local arborists and biologists. Now, more than ten years after the big decision was made to reforest her land, she says: “I just know this is what we are supposed to do on this kind of property.” Beate Popkin ______________________________________________________________________________

May 2022

The Bounty of Nature

Every year, at our chapter’s plant exchange in May, we benefit from, and – I like to think – participate in, the extraordinary liberality of Nature. Annie Dillard, in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, asserts that “Nature is, above all, profligate.” Nature, in her endeavor to assure the survival of life, routinely produces an abundance of seeds, suckers, rhizomous roots and vining branches, all of them in fierce competition with each other for space, nutrients, sunlight and water. The vast majority of these plant elements never amount to anything; they die long before reaching a state resembling maturity. But if we bring a viable piece of plant into our garden, it has a much better chance at survival. For a garden, by definition, limits competition; someone exercises control over the available resources. To an extent! For Nature still does her profligate thing in our gardens, giving us an abundance of seedlings and suckers to weed out and to share. This, I assume, explains why we love to exchange plants: we can be generous simply by following Nature’s lead. We can give freely, because what we give is free to us. Among the plants in my own garden that beg to be shared, purple phacelia (Phacelia bipinnatifida) ranks first. It’s a biennial flower of our forests that covers the small woodland behind my house with patches of purple carpeting that last for a month or more from mid-April to mid-May. It has moved into the sunnier front yard where it seems to do equally well. I know I shouldn’t just let all those seeds drop to the ground; they might smother everything in sight by next year’s summer. But its survival strategy seems fine-tuned to my infatuation with floral beauty: it gets ready to drop its seeds while it is still flowering. How can I possibly rip out all those phacelias, while they are still busy extending the spring wildflower season in my garden?

Among the plants in my own garden that beg to be shared, purple phacelia (Phacelia bipinnatifida) ranks first. It’s a biennial flower of our forests that covers the small woodland behind my house with patches of purple carpeting that last for a month or more from mid-April to mid-May. It has moved into the sunnier front yard where it seems to do equally well. I know I shouldn’t just let all those seeds drop to the ground; they might smother everything in sight by next year’s summer. But its survival strategy seems fine-tuned to my infatuation with floral beauty: it gets ready to drop its seeds while it is still flowering. How can I possibly rip out all those phacelias, while they are still busy extending the spring wildflower season in my garden? Purple phacelia is best shared in the form of seed during a narrow window in mid- to late May. It is true that the seedlings which emerge in early spring for the following year’s bloom can be transplanted, but since it’s a biennial plant they require some pampering. Not so with some of our other prolific self-seeders: smooth beardtongue, black-eyed susan, aromatic aster. These perennials can be easily dug up when they are small, plunged into their new location, watered once or twice, and left to assert their will to live. Smooth beardtongue is a fairly short-lived perennial, but the other two form persistent and widening clumps in addition to cropping up from seed everywhere in the garden. Our plant exchange thrives on such steady performers in the native plant landscape. But our participants always bring a great variety of plants. Every garden seems to have its own unique over- abundant species to share, so that we can feel bountiful and generous. Beate Popkin

Purple phacelia is best shared in the form of seed during a narrow window in mid- to late May. It is true that the seedlings which emerge in early spring for the following year’s bloom can be transplanted, but since it’s a biennial plant they require some pampering. Not so with some of our other prolific self-seeders: smooth beardtongue, black-eyed susan, aromatic aster. These perennials can be easily dug up when they are small, plunged into their new location, watered once or twice, and left to assert their will to live. Smooth beardtongue is a fairly short-lived perennial, but the other two form persistent and widening clumps in addition to cropping up from seed everywhere in the garden. Our plant exchange thrives on such steady performers in the native plant landscape. But our participants always bring a great variety of plants. Every garden seems to have its own unique over- abundant species to share, so that we can feel bountiful and generous. Beate Popkin

April 2022

Lower Howards Creek Nature and Heritage Preserve

This April, our Wild Ones chapter offers a spring wildflower hike at Lower Howards Creek, as we did last year. All winter long, the forest at the nature preserve has been a drab grey-brown. Then, quite suddenly, and before the trees have shown any real sign of new life, the forest floor greened up and colors appeared: white, blue, lavender and yellow. Responding to ample winter rains and to the warming sunlight of lengthening days, wildflowers have rushed into bloom, attracting pollinators and producing seed. When the trees will finally leaf out and shade the ground beneath, these flowers will have completed their reproductive cycle. Some will go entirely dormant with no trace of them remaining by June. Virginia bluebells are among those spring ephemerals. They grow here in stunning displays along the creek. It is hard to imagine that this valley was largely bare of trees 200 years ago. Lower Howards Creek was among the earliest areas in Kentucky occupied by European settlers starting in the 1770s, with Fort Boonesborough just 2 miles up the Kentucky river on its south side. There many early pioneers sheltered from the attacks of Indians who protected their hunting grounds from the intrusions of white people. Since the mid-eighteenth century, no native peoples had lived in Kentucky, but Shawnees and others came here regularly for seasonal hunts, mostly from across the Ohio river. The meat they procured in Kentucky substantially added to the food they harvested from the gardens around their villages up north.

and before the trees have shown any real sign of new life, the forest floor greened up and colors appeared: white, blue, lavender and yellow. Responding to ample winter rains and to the warming sunlight of lengthening days, wildflowers have rushed into bloom, attracting pollinators and producing seed. When the trees will finally leaf out and shade the ground beneath, these flowers will have completed their reproductive cycle. Some will go entirely dormant with no trace of them remaining by June. Virginia bluebells are among those spring ephemerals. They grow here in stunning displays along the creek. It is hard to imagine that this valley was largely bare of trees 200 years ago. Lower Howards Creek was among the earliest areas in Kentucky occupied by European settlers starting in the 1770s, with Fort Boonesborough just 2 miles up the Kentucky river on its south side. There many early pioneers sheltered from the attacks of Indians who protected their hunting grounds from the intrusions of white people. Since the mid-eighteenth century, no native peoples had lived in Kentucky, but Shawnees and others came here regularly for seasonal hunts, mostly from across the Ohio river. The meat they procured in Kentucky substantially added to the food they harvested from the gardens around their villages up north.

By the early 1790s, the Indian communities in Ohio and Indiana were so weakened that they could no longer mount threatening incursions into Kentucky, and pioneer settlers began to farm and build homesteads in the open country including the Lower Howards Creek valley. They also established industries, above all grist mills, flower mills and saw mills, all powered by the swift running creek. Access roads were built for the customers of these businesses and their products. While all this development affected the natural ecosystem in and above the valley, the greatest impact occurred due to the deforestation of the valley. Wood was needed for everything: to build cabins, to mark off the new private properties with fences, to provide fuel for domestic and commercial use. But timber was also exported.

From about 1790 to the mid-eighteen hundreds, tobacco, flour, whiskey and other Kentucky products were shipped on flatboats down the Kentucky, Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Since the boats could not be brought back, they were disassembled in New Orleans and the lumber was sold. A boat yard for the building of these simple vessels stood on the Kentucky river close to the mouth of Lower Howards Creek. Its first owner and operator was John Holder, an early pioneer and military officer who had come to Fort Boonesborough in 1777. He participated in many raids against native Americans, became a major land speculator and eventually settled close to Lower Howards Creek. One of the trails in the preserve bears his name. European settlement of North America was extraordinarily destructive of the continent’s ecosystems and wasteful of its natural resources. The development of the Lower Howards Creek valley was no exception, a fact that we can easily forget as we marvel at one of nature’s great spectacles, namely the brief annual display of abundant wildflowers carpeting a forest floor. After the Civil War, when steam power replaced water as a source of energy, the valley’s economy declined. Its industries moved to higher ground near a railroad hub in Winchester and its roads fell in disuse. The forest regrew, though not to its former splendor. The wildflowers reasserted themselves, responding again to the old cycle of spring sunlight, summer shade and winter dormancy. Beate Popkin

February and March 2022

Gardens

All gardens, even the most formal, take their inspiration from Nature. Plants, which are living and growing organisms, give them their form and meaning. For native plant gardeners this connection with Nature is a far more serious matter than for others. They take pride in the fact that their garden belongs to a specific place on the planet earth. They acknowledge the existence of eco-regions, based on climate, topography and soil, and they think of their garden as an integral part of its region. They also recognize that a garden is not just about the plants that grow there – it is also about the wildlife it sustains.

But a garden is not a meadow, or a prairie, or a wetland, or a glade, or a forest. It consists of an arrangement of plants growing in soil that was once disturbed through human activity, and often quite recently so. It usually surrounds a dwelling. There are probably hard surfaces on the property: a driveway, paved walkways, one or several patios, platforms to house a/c units and trash cans. And all gardens have boundaries: visible fences or invisible lines running between survey markers.

Gardeners who are strongly committed to Nature may choose to ignore the limits they face in the form of walls and hardscapes. They may simply plant where they find available ground. But that does not usually result in a good garden. The challenge is to let the human-made features of a property guide the placement of desired plants. A paved garden walk can be framed by perennial flowers, grasses, shrubs, or a combination of all three; the height of the frame should relate to the width of the path. A front patio near the entrance door should receive special attention; perhaps it can be a bit more formal than the rest of the garden. Driveways are the stepchildren of landscape designers, who tend to leave turf grass on both sides for the convenience of stepping into and out of cars. But shrubs can be judiciously placed where no one ever needs to step. An a/c unit in need of disguise can be hidden by many different kinds of plantings; the trick is to make the planting look as if it belongs there.

Design ideas that use the limits posed by human habitation creatively make the garden sing. They convey a sense that the plants belong not only to their ecological realm – they also belong to a place in which humans invest their care, creativity and hope.

Native plant gardeners are fortunate in being able to work with a wide range of plants. Their plants don’t need to be showy (though many are) or evergreen. Their plantings usually follow Nature through the seasons providing ever new sights and experiences. Spring ephemerals signal the end of winter; in May migrating birds sing from oak trees attracted there by the abundance of caterpillars feeding on their young leaves; throughout the summer the garden hums with bees, wasps, bugs and beetles, all attracted to the many flowers in bloom; and the colors of fall asters followed by the changing leaves of shrubs and trees amount to an annual miracle.

There is always more than one possibility for arranging plants in a garden to produce this repeated spectacle. While better and not so good ways exist for using plants to enhance a property with its dwelling, boundaries and hardscapes, there is never a perfect way. Nobody would categorically say: “this walkway needs to have a border of Pennsylvania sedge”, or: “this patio should be surrounded by a succession of meadow phlox, purple coneflowers and New England asters.” There are dozens of options for each scenario, and happy gardeners learn to experiment and to be playful about making choices. There are as many gardens as there are gardeners, and perhaps it is this variety that makes visiting gardens so enjoyable. Visitors to well-loved gardens expect surprise, beauty and pleasure: a plant paired with an ornament in an imaginative way; a grouping of several familiar plants each of which enhances the others; a creative idea to both mark and disguise the property’s boundary with plants.

There are as many gardens as there are gardeners, and perhaps it is this variety that makes visiting gardens so enjoyable. Visitors to well-loved gardens expect surprise, beauty and pleasure: a plant paired with an ornament in an imaginative way; a grouping of several familiar plants each of which enhances the others; a creative idea to both mark and disguise the property’s boundary with plants.

For a number of years our Wild Ones chapter scheduled an annual garden tour. It was fun for our visitors, but it was also a lot of work for the garden hosts and the organizing team, and we ran out of energy for the program. This year we are trying something new. We are offering our Members and Friends the opportunity to visit several private gardens through the spring and summer. Seven courageous owners are opening their gardens for two or three hours, each on a different Saturday morning. Some are native plant purists; others prefer a mixture of natives and non-natives. One exuberant garden focuses on vegetables. Most are well established. The idea is to convey an impression of the variety of natural gardens in Lexington. We hope that these visits will be inspirational, instructive, and – above all – enjoyable.

Beate Popkin

December 2021

Getting Urban Trees Off to a Good Start

Lexington’s tree canopy has just received a boost that bodes well for its future. Trees Lexington!, an organization dedicated to promote the planting and care of trees in the city, conducted its second Tree Steward training program. On two Saturday mornings in November, 15 volunteers learned how to properly plant small bare root trees and to prune others that had grown a bit. The workshops were held at Martin Luther King Park on the North Side, and at Fields to Forest Tree Nursery owned by Wild Ones member Ann Whitney Garner. Taught by Stacey Borden and Wild Ones member Dave Leonard the two sessions were immensely instructive and very enjoyable. The volunteer trainees ditched in with shovels, pruners and tons of questions. It seems obvious that planting trees in Lexington’s parks, greenspaces and private properties – both residential and commercial – is crucial to increasing the city’s tree canopy. The Tree Stewardship program aims to develop a group of tree advocates who can see newly planted trees through their first years of growth and assure that they will become healthy good looking plants that last for a long time.

Often, when home owners envisions a new tree on their property, they end up with a specimen whose heavily truncated roots are contained in a very heavy root ball surrounded by burlap and possibly a wire cage. Due to its weight the tree must be planted by professionals which adds to its already high cost. Once in the ground at its new location, the tree will, for several years, put most of its energy into regrowing the roots that were cut off when it was dug up for transport, usually way over 50% of all its small feeder roots with which it absorbs moisture and nutrients. By contrast, a small bare-root tree (let’s say 4-5’ tall) planted in a proper-size hole, will produce significant top growth during its first season. Five years later its canopy will equal the size a ball-and-burlap tree planted at the same time. Best of all, anybody can plant a bare-root tree; no professionals are needed. And even better, small trees are inexpensive and Trees Lexington! periodically provides them free to homeowners.

But there is more to getting an urban tree off to a good start in its permanent location. Judicious and periodic pruning early in its life helps it develop a good structure, supports its health and assures that it lives well in its designated space. Pruning is a science and an art, workshop participants learned. Science-based rules apply pretty universally: don’t cut off more than 30% of a tree’s crown in a growing season; prune out deadwood; never leave stumps etc. The art comes in when the pruner must envision what the tree will look like when grown up, and there are choices to be made: how high up on the trunk should the tree eventually branch out; does one aim for a densely leafed crown or a more airy one? The Tree Steward workshops developed by Trees Lexington! are a great service to our community. Trained Tree Stewards can advocate for trees in the city, but they can do much more: they can lead volunteer groups in planting trees in public spaces, and they can advise home owners on getting trees started on their properties at minimal cost and then help them guide their trees through the first years. The workshops will be offered periodically for anybody who cares about Lexington’s tree canopy and wants to help improve it. In the meantime, check out Trees Lexington!’s terrific website.

Beate Popkin

October 2021

Loving Trees

Trees – they enhance our urban lives in so many ways. They allow us to live with nature providing food and shelter for insects and birds. Their roots absorb and channel vast amounts of rain water that cannot penetrate the ground when it falls on roofs, patios, driveways, streets, sidewalks and parking lots. In doing so, they also process many of the pollutants that cities generate and they help to keep streams and rivers healthy.

What I cherish most about trees is their shade. Walking along a tree-lined street on a hot sunny day, or getting into a car that is parked under dense foliage, or sitting in an outdoor café where shade comes from a leafy canopy – these are comforts to help me cope with our merciless summer heat.

Such comforts are not abundantly available in Lexington. True, there are some tree-lined streets in the city with relatively safe sidewalks, and occasionally I do find that parking space under a tree for which I am always on the look-out. When it comes to enjoying a meal or a glass of wine under the canopy of tall trees – well, all of us who have done just that at Michler’s Native Café know how rare it is in Lexington and how much we yearn for more public spaces like this.

We have ample rainfall in the Bluegrass and our fertile soils support a rich variety of trees. Why does it seem so difficult to harness these resources for creating a more richly treed city? Three reasons seem to stand out. There are the wires running both above and below ground and the underground pipes needed to service urban homes and businesses. They limit where trees can be grown.

Two other reasons for our relative dearth of trees are less compelling. One has to do with advertising: businesses along major roads want their signs to be visible, which results not only in treeless, but also in very ugly urban spaces, since each sign aims to outcompete its neighboring sign. Trees could provide relief from this visual assault, but if they are allowed at all, they must be small or spindly – essentially invisible. In an era when advertising is rapidly moving to the internet, this kind of urban landscape should become obsolete, but Lexington is still embracing big-billboard promotions.

Private properties are, in principle, more amenable to trees. In the past, before air-conditioning, homes were designed and spaced to make room for shade trees to provide cooling. Home-owners cherished those trees and invested money and work into maintaining them. But that seems like a habit of the distant past now. How often have I heard of the nuisance that trees cause, because their leaves must be raked, twigs that drop from them must be picked up, their fruit is messy, they heave up sidewalks, they appear to endanger a structure (a belief rarely confirmed by asking an expert). Trees seem unnecessary to human lives glued to a cellphones or TV screens.

Tree Week, now in its fourth year, attempts to change that attitude, to teach us all to love trees again, to embrace the benefits they provide to urban spaces and to find meaning in the occasional work they require.

Beate Popkin

_____________________________________________________________________________

September 2021

Land Management at Josephine Sculpture Park

In the mid-1960s Melanie VanHouten’s family purchased a 100 acre tobacco farm just outside Frankfort, Kentucky. In 2008 Melanie and her husband began creating the Josephine Sculpture Park on 20 acres of the original farm, an additional 10 acres of the original farm was added to the park in 2018. At that time, no family had lived on the farm for several years. Some dumping had been done on the property and invasive species had become well established, especially Honeysuckle and Callery pears. The JSP website states the mission of the park: Our mission is to connect people to each other and the land through the arts. We provide creative arts and nature education to our community and transformative opportunities to artists while conserving the beauty of Kentucky’s native, rural landscape. Creating a sculpture park was a non-traditional way to use the property and share it with the communi ty. This involved not only developing the sculpture/art aspect of the park but also managing the property to preserve, repair and enhance the natural environment. In a 2021 video available on the JSP website, Melanie VanHouten outlines the challenges of managing the natural habitat of the park as a part of the mission. This video provides insight into the JSP team’s is work as they face the challenges of managing the natural habitat. Josephine Sculpture Park (JSP) opened to the public in 2009 with 10 sculptures. I remember visiting it in the early days. It was difficult to find and we were the only visitors that day. Today JSP has over 80 works of art and has included artists from around the world in their Artist in Residence program. In addition, JSP offers art and environmental education through workshops, camps and school field trips to the park. Visiting JSP is free and can be done from dawn to dusk 365 days a year. In 2019 our Wild Ones chapter awarded a Public Garden Grant to JSP; we visited in the late summer 20